with Matias Busso, October 2024.

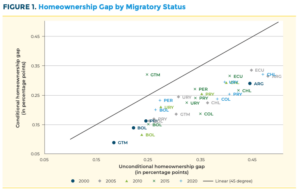

Urban migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean are significantly less likely to own homes compared to residents, with demographic factors accounting for about one-third of this homeownership gap (HOMG). Compared to local residents, migrants tend to have less living space and fewer housing amenities like rooms and cooking areas, and they have uneven access to services like water and sewage. Optimizing existing housing stock and developing rental marketse.g., by streamlining processes while upholding quality and safety standardsare key strategies to support migrants in securing housing and enhancing job access.

How Does Internal Migration Shape Urban Growth in Latin America and the Caribbean?

with Matias Busso and Paul E. Carrillo, June 2024.

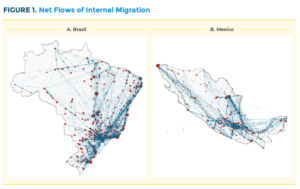

While international migration in Latin America and the Caribbean surged over 80% between 2015 and 2020, internal migration remains the key driver of urban growth. Internal migrants choose a variety of urban areas, not only major cities. The share of internal migrants in the local population is relatively even across cities of varying sizes. Because institutional capacity to implement effective policies in response to migrant inflows varies across cities, some local governments may require additional support from other levels of government to seize the opportunities and address the challenges of urban migration.

Can Electoral Incentives Explain Gender Differences in Leaders’ Behavior?

with Clemence Tricaud, August 2023.

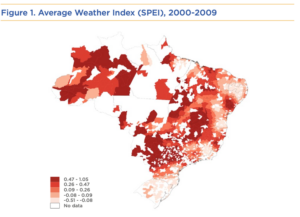

Female and male mayors in Brazil responded differently to the COVID-19 crisis, with effects on mortality that varied over time. In the early months of the pandemic, female-led municipalities were less likely to close essential businesses and had higher COVID-19 death rates compared to male-led municipalities. Towards the end of the year 2020, however, female-led municipalities were more likely to close essential businesses and had fewer COVID-19 deaths than male-led municipalities. This suggests that female and male mayors handled the crisis in distinct ways, with implications for understanding gender differences in policymaking and crisis management.

with Matias Busso, April 2023.

Cities that received more migrants observed faster growth in employment and a slower increase in wages. The wage effects are stronger in the service sector, likely due to its higher degree of labor informality. The stock of precarious housing units increased in cities receiving more rural migrants, rents for this type of housing did not increase, suggesting that supply kept pace with migration-driven growth in demand. Non-precarious housing experienced faster growth in rents but slower growth in quantities in cities that received more rural migrants. This is consistent with cities having a limited supply of land for housing.

What Can Latin American Local Governments Do to Improve Public Health?

March 2023.

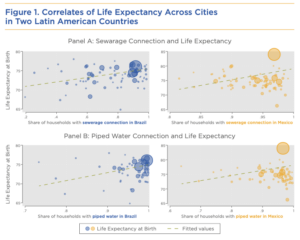

Health outcomes can vary significantly across cities within the same country, and within neighborhoods of the same city in Latin America and the Caribbean. This variation is partly explained by aspects of the urban environment that can be shaped through local policy. Public infrastructure investments, especially those in water, sanitation, and public transportation, have well-documented positive effects on local public health. Lower-cost interventions can also improve local health outcomes. These include zoning policies to protect people from negative externalities, the enforcement of road safety regulations, and the building of open public spaces to promote walkability and healthy lifestyles.

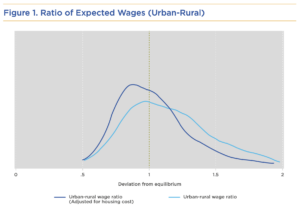

Do People Continue Migrating to Cities for Higher Wages despite Potentially Worse Living Conditions?

with Matias Busso and Nicolás Herrera L., December 2021.

Despite high levels of urbanization, economic incentives to migrate from rural to urban areas persist. In addition to the expected urban-rural wage gap, both the likelihood of securing formal employment and the higher cost of urban housing also play a significant role. The urban-rural wage gap is larger for individuals with higher levels of education and is greater among men than among women. This wage gap is smaller when the city is closer to its rural geographic area of influence, in cities better equipped to absorb migratory flows, and in rural areas with a higher proportion of young people (who tend to be more mobile).

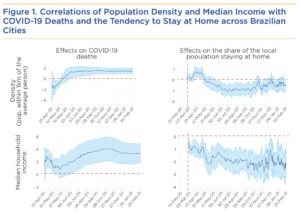

Why Has COVID-19 Affected Some Cities More than Others?

December 2021.

Some variables related to the impact of COVID-19 at the city level are similar across very different contexts. In both Brazil and the United States, for example, population density is associated with a higher number of COVID-19 deaths per capita. Other variables related to the local impact of the pandemic behave differently depending on the context. In Brazil, cities with higher average income levels saw relatively fewer people choosing to stay home and more COVID-19 deaths, whereas in the United States, the opposite was observed. Cities with higher levels of socioeconomic vulnerability in Brazil experienced more deaths per capita despite a greater tendency of their populations to stay home during the early months of the pandemic.

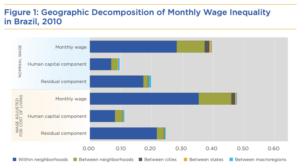

How Does Residential Segregation Shape Economic Inequality, and What Can Policymakers Do about It?

with Julián Messina, January 2021.

In Latin America, average wages vary greatly between countries richest and poorest regions. Differences in average wages across neighborhoods of the same city are even more significant. Residential segregation reduces access to economic opportunity. Families in less accessible neighborhoods spend more time and money commuting, are less likely to apply to distant jobs, and are more likely to remain unemployed if they lose their job. Public transportation investments can help to improve access to economic opportunity and reduce inequality in segregated cities if they are combined with zoning policies that allow for flexible housing supply in beneficiary neighborhoods.

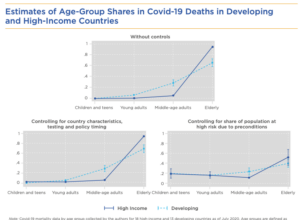

with Annabelle Fowler and Nicolás Herrera L., December 2020.

Young and middle-aged adults represent a larger share of Covid-19 deaths in developing countries -including Latin America- than in high-income countries. This is not due to those countries younger populations. Much of the gap is explained by lower recovery rates among non-elderly adults, which are linked to a high prevalence of preexisting conditions associated with severe Covid-19 complications, and in some cases by limited access to life-saving intensive care. Higher infection rates also appear to play a role, as factors correlated to faster virus spread -including housing overcrowding and labor informality- are likewise correlated to non-elderly Covid-19 mortality.